© F. Siebold/berlin.de

Holocaust Remembrance: A Stolperstein and a Stack of Letters

The life and abrupt end of Gertrud Kirsch, a Jewish widow who ran a boarding house in Berlin, is retold in letters to her daughter, Helga, whom she had sent ahead to safety in Britain. Markus Hesselmann wrote down the story of those letters.

“If you write to Shanghai, please tell them to get in touch with me.” That was the last sentence of the last preserved letter Gertrud Kirsch sent to Helga on October 27, 1941. Two years before, Gertrud, a 46-year-old Jewish widow, had sent her 18-year-old daughter to safety in London.

She herself was forced to remain in Berlin, denied an entry permit into Great Britain. Her mention of Shanghai sounds hopeful. Many Jews went to Shanghai at the time to flee the Nazis.

Ursula Krechel, a German writer who lives around the corner from the house on Güntzelstrasse where Gertrud Kirsch once lived, tells the stories of Jews who had fled to China in her novel “Shanghai fern von wo,” which in English means: Shanghai, Far From Everywhere.

“Hope” is a recurring theme in Ms. Krechel’s book: The hope of making it out of Germany, but also the hope of getting out of “the waiting room that was Shanghai” after the Japanese, Nazi Germany’s allies, marched into the city.

Relatives and friends of Ms. Kirsch had managed to escape or “depart.” Departed was used at the time to describe the forced emigration in letters that were routinely censored. Many of Berlin’s Jews “departed” to the United States, South America, Shanghai and to Great Britain.

“Everyone is going to London; it’s become a second Berlin,” Ms. Kirsch wrote.

But for Gertrud, the hope of escaping to China was no longer realistic. It was only after the war that her daughter was able to contact the relatives who had fled to Shanghai. In Berlin, October 1941 marked the first three deportation trains that departed from the Grunewald train station in its city’s wooded southwest, taking more than 3,000 people to the Jewish ghetto in Lodz, Poland.

Hermann Göring had already ordered Reinhard Heydrich to prepare for the “final solution of the Jewish question.”

In Berlin, October 1941 marked the first three deportation trains that departed from the Grunewald train station in its city's wooded southwest, taking more than 3,000 people to the Jewish ghetto in Lodz, Poland.

A ban on Jewish emigration from Germany had taken effect on October 23.

By that point, many Berlin Jews were already living in overcrowded apartments in so-called jews flats.

© Familienarchiv Lemer/Anders, London

Journalist Inge Deutschkron, who lived a few doors down from Gertrud Kirsch on the corner of Bamberger Straße and Güntzelstraße, later described her experiences in a speech to the German parliament and in a book titled “I Wore the Yellow Star.”

Staying on in Berlin, Gertrud Kirsch continued to run her boarding house on Güntzelstrasse.

She mentioned it proudly but discreetly in her letters, describing her Jewish “boarders” as contemporaries who were involved in her life. The building, at No. 62 Güntzelstrasse, is still a boarding house today.

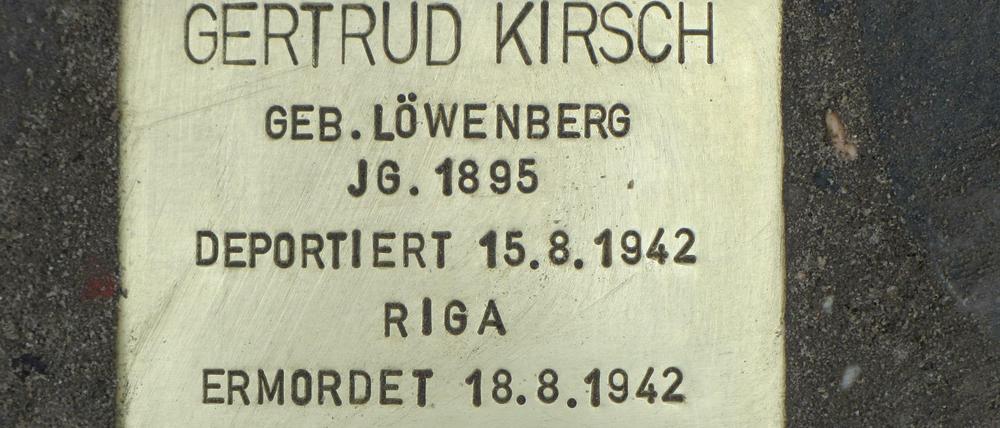

The inscription in German reads: “Here lived Gertrud Kirsch, née Löwenberg, born 1895. Deported August 15, 1942, Riga, murdered August 18, 1942.” In her letters, she repeatedly mentioned the British consulate and the “permit” she was trying to obtain.

She wrote about her constant visits to the consulate in Berlin, about papers that couldn’t be found, about the German employment office, about the Jewish benevolent society interceding on her behalf, and about a sluggish bureaucracy, which she repeatedly described as “comical.”

She wrote that she had completed a few English lessons and she wrote of the “money” she dreamed of making in England, perhaps with her own boarding house, which she had been told would be easy to open there.

But when World War II began on September 1, 1939, followed by Britain’s declaration of war against Germany, her hopes of going to London were dashed. Even before then, she wrote critically about other possible destinations.

“Things are not that easy in America,” Gertrud Kirsch wrote. “But I would go to New Zealand immediately.” Or, as she later wrote, to Shanghai.

There is a diffident undertone in the otherwise consciously – or perhaps unnaturally – optimistic flow of a letter she wrote to her daughter on the first day of the war.

“Today, once again, I was overjoyed to hear news from you. Who knows how much longer it will be.”

Soon her tone became more urgent.

“Well, my child, I would like to ask you to see if someone, somewhere, could vouch for me. I could also wait for Switzerland. As you can see, nothing is happening with the United States,” she wrote in April 1940.

In her Berlin surroundings, she added, “the circle is getting smaller and smaller,” and one person after the next was “departing.”

Well, my child, I would like to ask you to see if someone, somewhere, could vouch for me. I could also wait for Switzerland. As you can see, nothing is happening with the United States.

In March 1940, Gertrud Kirsch described her birthday party with “all the boarders.”

“I didn’t go to bed until 2:30 in the morning, so you can imagine how nice it was,” she wrote. “I hope we can celebrate this day together next year.”

Then, once again, she returned to the illusory safety of everyday life, writing about how busy she was.

“As you know, my dear child, I have a business to run,” she wrote.

© Barbara Anders

In May 1941, Gertrud Kirsch appeared to write reassuringly to her daughter: “I have nothing but good news to report about myself. Please don’t worry about me at all. I am doing very well.”

“Dear little one, I will leave you to your affair of the heart, and I hope we can celebrate the engagement together,” Gertrud Kirsch wrote in the last preserved letter, just a year before her death.

Her daughter Helga had apparently fallen in love in England. The letters that arrived in England, written with great caution and heavily censored, are a constant balancing act between Gertrud’s desire to leave Germany and see her beloved daughter again, and the will to show that she was doing well in Berlin and that things would eventually take a turn for the better.

“Despite the fact that I have everything I need here, I would be overjoyed to be with you,” she wrote in a letter dated May 13, 1939, a month after her daughter had boarded a ship in Hamburg for England.

From the first to the last letter, she insisted that Helga should not worry about her. However, she did complain that she was not receiving letters from London.

During a visit to London by the Tagesspiegel author, who became acquainted with the Lemer family during the commemoration at the stolperstein in Berlin, Helga Lemer, now 95, talked about the letters from her mother, which she would so much like to read again, and gave Tagesspiegel copies.

The letters are written in a small, poorly legible handwriting, and also in Sütterlin script, a historical form of German handwriting. Toward the end, the Sütterlin was mixed with Latin script.

Ironically, the Nazis had prohibited Germans from continuing to use what was widely referred to as the “German people’s script.”

Hardly anyone can read Sütterlin today, including the transcription service at Tagesspiegel. To do so, the newspaper enlisted the help of Christiane Timper of the Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf district office.

Her mother, Anne Timper, knows Sütterlin and was willing to dictate the letters on tape, so that they can be typed and sent to Helga Lemer. “I was able to read the letters out loud to my mother,” writes Barbara Anders from London. “They are so interesting and similar emotionally.” The original letters are to be preserved for posterity in a Berlin archive and, like the stolperstein, serve as a remembrance of Gertrud Kirsch.

- Bayerisches Viertel

- Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf

- England

- Flüchtlinge

- Großbritannien

- Holocaust: Alle Beiträge zum Themenschwerpunkt

- Nationalsozialismus: Historischer Schwerpunkt

- Stolpersteine

- Zweiter Weltkrieg und Kriegsende

- showPaywall:

- false

- isSubscriber:

- false

- isPaid:

- showPaywallPiano:

- false